Fervo Energy

Tapping into the heat beneath our feet to provide gigawatts of clean energy

The 2025 edition of the DCVC Deep Tech Opportunities Report, released in June, explains the global challenges we see as the most critical and the possible solutions we hope to advance through our investing. This is a condensed version of the first section of the report’s third chapter.

Meeting electrical demand from data centers, electric vehicles, clean hydrogen generation, steelmaking, cement manufacturing, cryptocurrency mining, desalination, and other emerging sectors will require a range of generating solutions tailored to the specific needs of each region and industry. Most renewable sources can’t yet match the cost-effectiveness of combined-cycle gas-fired power plants, but onshore wind farms and solar photovoltaic facilities are catching up fast, according to a 2024 report commissioned by the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

DCVC Climate backs companies with bold, proven ideas for continuing to bring down the costs of other types of zero-carbon energy, including predictable baseload power. One of our most exciting investments is Fervo Energy, a leader in enhanced geothermal energy. There’s an astonishing amount of heat energy trapped below our feet, yet it’s difficult to tap, and so geothermal energy currently accounts for only 0.4 percent of electrical generation in the U.S. Fervo uses techniques adapted from the oil and gas sector, including horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and fiber optic sensing, to reach pockets of geothermal heat previously considered inaccessible.

Fervo activated its first commercial well in 2023, achieving record flow rates and supplying 3.5 megawatts of electricity to a Google data center in Nevada. Now the company is in its scale-up phase, building a 500-megawatt power plant called Cape Station in southwest Utah. Fervo has already lined up hundreds of millions of dollars in new equity financing, credit, and loans — not to mention purchase agreements with big customers who are eager for sources of clean firm power.

“Their first project has operated for over a year now, and they’ve proven it’s steady and doesn’t have thermal declines outside of what they predicted,” says DCVC partner Rachel Slaybaugh. “They’re proving that they can capitalize these projects in a sustainable way. In 2026 they’ll be able to put megawatts on the grid. They have a long project pipeline, with a big jump on lease holding — which is great, because now a lot of people are trying to get geothermal leases. Piece after piece, they’re doing the things they said they were going to do.”

There are also other technologies that promise to provide predictable power and smooth out the bumps in the supply of wind and solar energy. One is thermal storage — and in this area we’re backing a company called Fourth Power, built on the work of MIT mechanical engineering professor Asegun Henry.

The idea of thermal storage is to siphon electricity from the grid during periods of excess production and low prices, store it for hours or days in the form of heat captured in large graphite blocks, then turn it back into electric power when demand and prices are higher. To make all of that practical at scale, Henry developed an innovative liquid-metal circulation system that transfers thermal energy from electric heaters into the graphite blocks, and then carries the energy back out when needed to thermophotovoltaic towers, where it gets converted back into electricity. The Massachusetts-based company is currently testing each of these components in the lab, while getting ready to build its first commercial pilot plant. The materials that go into Fourth Power’s design, like tin and graphite, are far cheaper than those needed for competing storage technologies such as lithium-ion batteries. That’s why the company expects it will be able to deliver electricity for $25 per kilowatt-hour (when paired with a renewable power source), less than a tenth the cost of power from gridscale chemical batteries — and on par with the cost of power from gas-fired generating plants.

Soaring electricity demand has also revived conversations about one more source of clean firm power: nuclear. In September 2024, Microsoft struck a 20-year deal with Constellation to buy power for its data centers from a revived Unit 1 reactor at Three Mile Island, while TerraPower, founded by Bill Gates, announced it had inked an agreement to sell power from its advanced nuclear project in Wyoming to Sabey Data Centers. But 100-megawatt-plus reactors like these are still notorious for their high capital expenses and operating expenses. Another way to power data centers or other key facilities is to build smaller, more efficient reactors on site. Oklo — which went public last year, six years after DCVC’s first investment in 2018 — says its first Aurora liquid metal – cooled fast reactor will come online before 2030. These reactors, which use nuclear waste as fuel, are designed to provide 15 to 50 megawatts of power, perfect for a data center. Oklo said in December that it has signed an agreement with Switch, an operator of large data centers in Georgia, Michigan, and Nevada, to deploy enough Aurora reactors to generate up to 12 gigawatts of power through 2044. And it said in January that it has inked a deal with natural gas generator supplier RPower to roll out a “phased power model” for data center customers even sooner. Under the deal, gas generators deployed to data center sites by RPower would be replaced by Aurora powerhouses as they become commercially available.

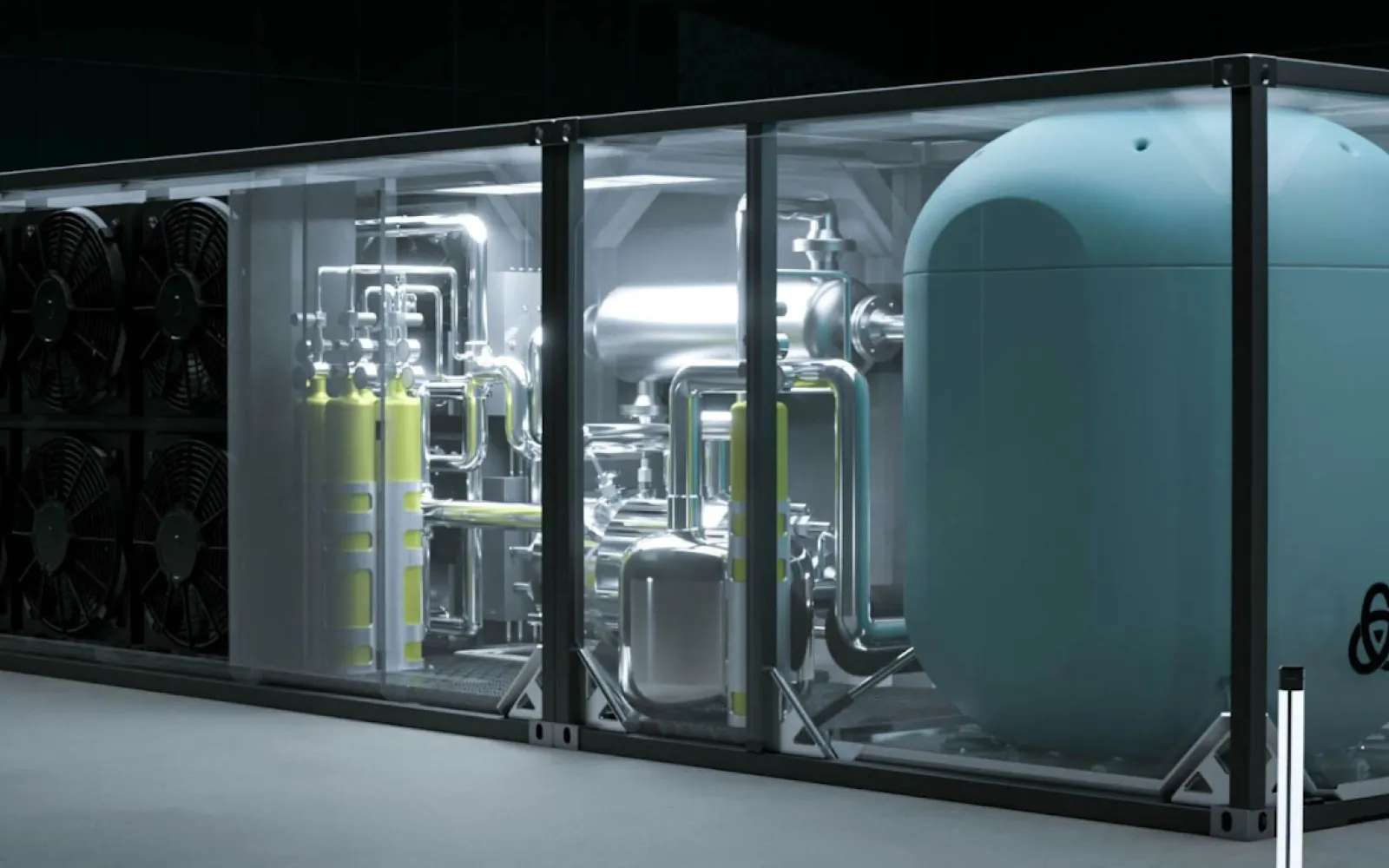

An even smaller and more portable fission reactor called Kaleidos is under development at DCVC-backed Radiant. Kaleidos will be small enough to fit on the back of a semitrailer and will generate about 1.2 megawatts of power, making it a suitable power source for a small hospital, a military facility, or an emergency command center, replacing dirty and noisy diesel generators. Since we last discussed Radiant in our 2024 Deep Tech Opportunities Report, the company has secured $166 million in new funding in a Series C financing round led by DCVC; successfully completed a passive cooldown test demonstrating that Kaleidos can safely shut down and cool off without power; and finalized plans to test a Kaleidos prototype at U.S. Department of Energy’s Idaho National Laboratory in 2026.

“Radiant is exciting because they’re showing that you can get something done in a reasonable amount of time with a reasonable amount of money,” Slaybaugh says. “Their team is on fire to go build stuff. ‘Let’s get building, let’s get moving’ is a new narrative in an industry that has maybe struggled to do that.”

Now that the AI revolution and the electrification of industry and transportation are creating unprecedented power needs, the demand for zero-carbon electricity is finally catching up to the vision of innovators in areas like next-generation nuclear power, geothermal power, and thermal storage. We’ve been proud to back these innovators for many years, and we can’t wait to see what kinds of further advances their ideas unlock.

Tapping into the heat beneath our feet to provide gigawatts of clean energy

Building thermal energy storage technology to buffer the grid, as variable electricity sources replace polluting ones

Zero-carbon energy from advanced nuclear fission

Building a portable nuclear microreactor to replace diesel generators